2/9

I was thinking it could be fun to somehow very specifically link up notes and colors. I don't know how easy that is to accomplish. Something like this below video that I found:

It seems to be mapping the sounds very specifically with the colors. So it is not triggering them through analyzing the sounds on the other end, but rather triggering an associated visual every time a sound is played... So it's not so much audio reactive but "input reactive".. Would it be possible to have a slightly different visual for a range of up to ~127 individual inputs?

I also would like to somehow trigger light in or on crystal singing bowls when they are played... possibly with projection mapping? Or, the bowls could also turn on a physical light inside them when I hit them with a mallet (though it might make the bowls vibrate sonically to have a light inside them, so would have to think of a way to do it that wouldn't affect the sound). But that would be a different scenario...maybe in tandem with the algorithmically generated music and visuals which are responding to the notes. Possibly the bowls could also be affecting the projections so there is a symbiosis there as well. Here is an example of someone doing something similar (but with lights that change color, and without turning off):

Update 2/12 (for LIPP)

I have been reading a lot and thinking about the kinds of systems that I would like to work on in general and using the tools in our class.

I am definitely very influenced at the moment by the Light and Space artists I am reading about for Recurring Concepts in Art, and installations by James Turrell and others who work with perception. I would like to create something in this school or vein but also with incorporating sound, and slowly fading in between a series of "places" that create an arc of experience. So the key word is "slow" - but constantly moving and shifting, maybe with some central focus point that could also have elements be introduced or taken away or faded away rather than flashing in and out which seems to be what a lot of video effects are about...

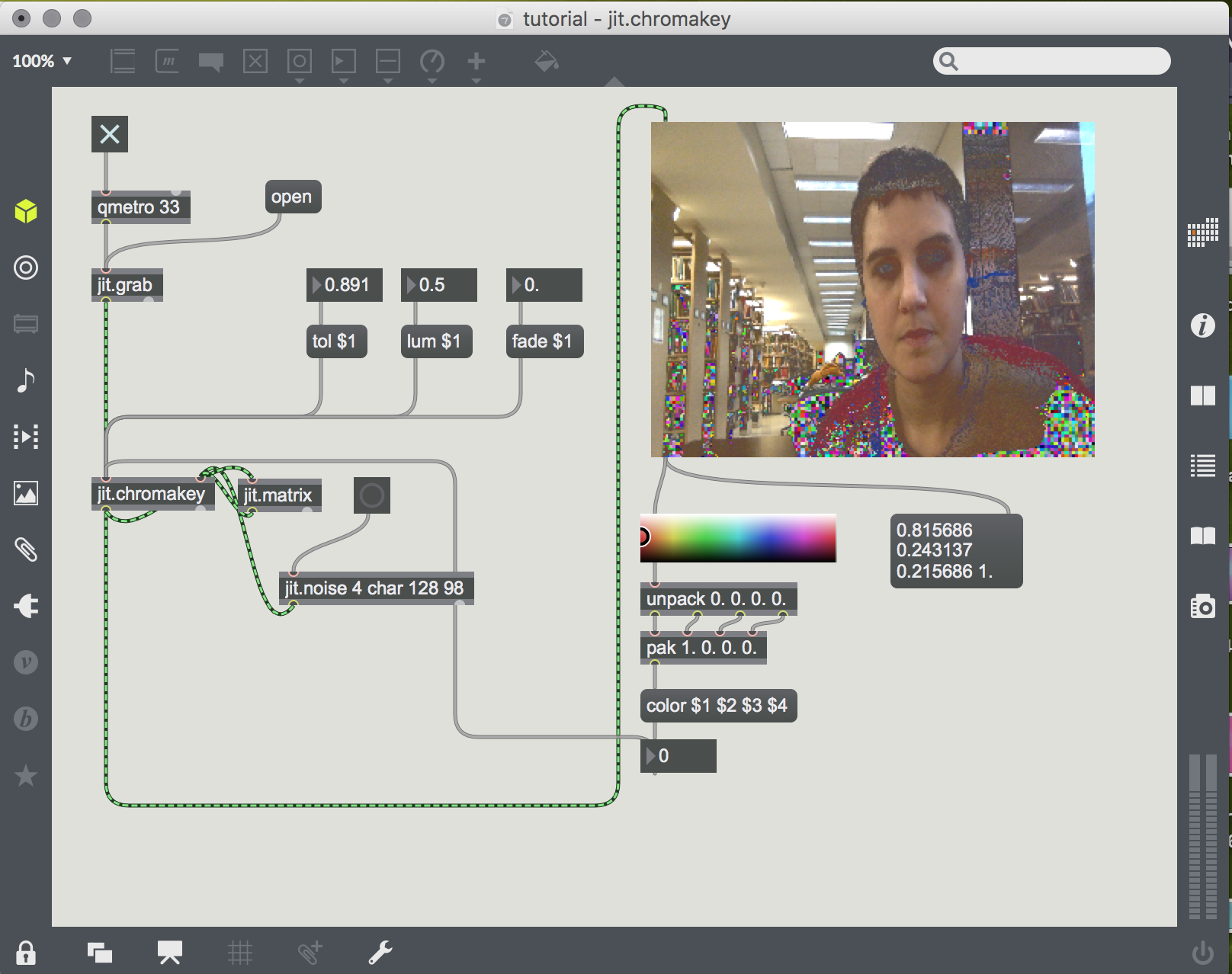

I also realize that a lot of figuring this out will also be from raw experimentation, and I still need to do a lot more of that. I have been following the tutorial videos for our class but have not worked much more on my own Max patch yet(!), but plan to really get into it over the next two weeks. I still need to work more with the jit.smooth function, I tried to add it but it turned orange, so I was wondering if we could go over this in my office hours appt with you (this Friday from 2:40-3pm)?

I attended two live audio-visual performances this past week, the one at 3 Legged Dog last Saturday, and one this past Saturday as well at Spectrum in Brooklyn which I was also playing music in, where a video artist did live visuals for each of the 4 acts, and I was wondering if I could do a review of some kind of amalgamation of a few sets from different shows instead of just one event. Other than being a little stuck with Max at the moment I have been feeling inspired by various things in relation to our class!

Bobst library stacks w/ jit.lumakey tutorial